‘What if we rode down the hill and then off the ramp?’ I said to my little gang of friends on push bikes. I was twelve years old, and we had been riding through puddles, and holes and up little hills racing and chasing despite the threats from our Mum and Aunty.

‘Don’t you dare get dirty before football.’ They said.

We looked down at the loading ramp for fuel trucks below us, our bikes all in a row. Who was going to ride down and take the jump at the end of the ramp?

‘I dare you,’ my brother said.

‘Yes, I dare, I dare, I dare,’ they all added. It did look very scary but, in those days, no-one said No to a dare. I had seen the motorbike cops on TV riding their bikes across bumps and holes and I thought perhaps I could do the same. The two could not be more different—strong men with thick wheels, and a little girl on a push bike—but still a dare was a dare. It was important to be brave, to show courage and never to ‘wuss out.’

Deep breath and down I sailed, the bike dropped, I flew high in the air and fell on my right shoulder. I heard a loud crack and stumbled up in the sand, my front tyre all bent up.

In shock I walked home to the house where my Mum and my Aunty were getting the younger children ready to go to football. It was Saturday morning, and the little kitchen was all Weetbix, babies in highchairs, face washers and sandwiches. I struggled through the door and fell into a chair.

‘Oh no, now what’ my mother said. ‘Why do you have to do such silly things?’

My Aunty the nurse showed some more sympathy. She always spoke very quickly and repeated phrases many times. The sight of my ashen face set her off. ‘Oh, my goodness, look, look at this arm,’ she said. I was holding it to my body and the pain and shock started to kick in. ‘Hospital, you will have to go to hospital. Yes hospital. No point, no point he’s playing golf, it’s B Grade Championships. He won’t miss golf.’

The golfer was the only doctor in town, and I had recently been to see him about a fishbone caught in my throat one Friday night. I was in trouble for swallowing a fish bone and spent hours out on our veranda eating lumps of bread to push it down. Our family farm was at least half an hour from the hospital, and a trapped fish bone was not enough reason to travel, at least not straight away. Finally, having run out of options and probably bread I was bundled into the car and a very grumpy doctor was called in from his house. A long pair of pliers down my throat, vomit all over the floor and the bone was gone. Mum kept apologising for the mess. Trembling and holding my arm I knew this time we would deal with more than vomit.

My Aunty rang the golf house, left a message and then it was all about the mohair jumper. I was wearing a tight new and bright red mohair jumper-Patons 631, 8 ply mohair jumpers for boys and girls– ‘nothing really very simple pattern I can loan it to you,’ Mum would have said that day when she met her friends but secretly very proud of her creation.

Brandishing some scissors my aunty said, ‘Oh, Barbie you look so pale, so pale it must be so sore, here Kit (my Mum) cut, cut the jumper.’

‘No, no!’ Mum shouted, ‘we can’t cut it I have just finished knitting, it’s mohair, expensive wool.’ Together they carefully prised the tight jumper off with my good arm up over my head and then slowly started on the other. Mum gave it a quick tug; I screamed and fell to the floor in a clammy faint. Agony, bright red searing pain riveting through my arm.

Just then my Uncle Jack arrived from the golf house to say the doctor had the message and would come to the hospital after he finished his golf and set the break. Uncle Jack was an ambulance driver and gently gathered me up and took me in his car to the hospital.

I can still remember that hospital bed, the pale cream curtains, the cold lino and the pain, the relentless excruciating pain. In the evening the doctor was probing. Serious voices near my bed. It was a jumble of talk to my stunned mind; a doctor in Melbourne saving the arm; an aeroplane arriving in the morning.

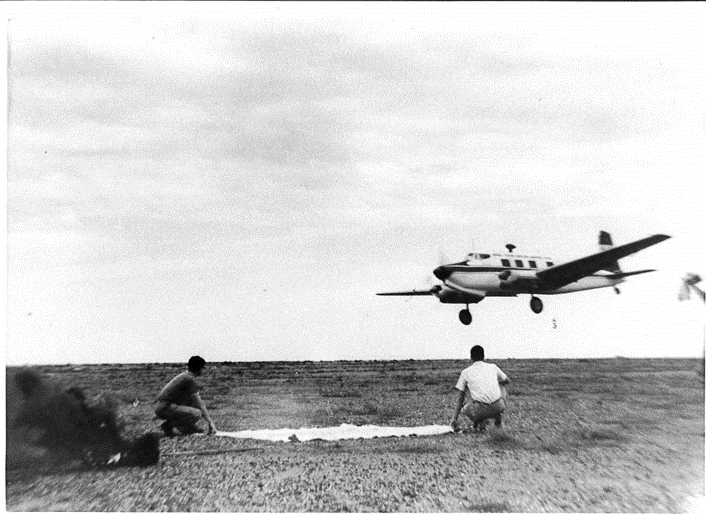

My Uncle Jack had built a runway in his paddock close to town for emergencies. I heard talk about the fallow paddock (ploughed up and ready for sowing.) The ploughing meant either end of the runway was very bumpy for the pilot and passengers. Mum and my brothers came to the hospital in the morning, and we heard the roar of a plane. More white-hot torture as I was moved into the local ambulance to go to the plane.

Then the air ambulance nurse spoke directly to me. With kind eyes she said, ‘We are going to Melbourne, and I will be with you all the way.’ I fell in love with her and felt a sense of hope with her hand in mine-strong, warm, resolute. ‘I am going to give you a needle and you will sleep.’ She turned to the doctor and said, ‘Get the dad to say goodbye, pass the morph.’ My Dad kissed me, moist eyes.

I went into a deep sleep and woke up strapped to the floor of a plane shuddering, noisy and so frightening. The nurse angel was there still holding my good hand and started to explain what would happen next. The plane landed and more pain spasming through my body. The ambulance men seemed huge at the door of the plane. Big smiling bodies quickly sliding the bed into the vehicle. It was warm inside with sun coming through the windows. I could see outside. The nurse said something in medical speak to the ambulance men.

The driver looked at me and said to his friend, ‘Let’s try the long way home.’ I was strapped in, and they eased the vehicle along the tarmac. Once they reached the main road the driver moved the wheels on one side into the tram tracks. It was a blur of traffic, sirens, and donging trams. Despite the pain I felt so loved and special as the ambulance men cracked jokes whenever a tram came close clanging away.

‘We might get off here, everyone this one is a bit bigger than us’ the driver would say laughing and then we would wait for the tram to pass.

At the hospital there was a big crowd to meet me again and I can’t remember anything more until I woke in bed with a brace around my tummy and a piece of soft metal holding my arm at right angles.

I was entranced with the nurses at the hospital. They seemed so beautiful soft pink and white uniforms with their little peaked hats and hair all caught up in a French bun. My bed looked out over a garden, and I could watch the stairs of the nurses’ home to see who would be on duty next.

When I was discharged there was a procession of doctors and nurses lining the corridor and some were crying. I remember saying to my Mum, ‘Why are they crying?’

She said, ‘I think they got very fond of you Barb while you were here.’

More than 50 years on my family still laugh about my little arm and how I swim in circles. I know now that the main knob of the shoulder bone was smashed and the long arm bone nearly protruding from my skin. My arm has stayed about the same size it was when I was 12 years old, and luckily, I am not a very big person, so most people don’t know. I have tracked the ambulance journey from Essendon to East Melbourne and it was about fourteen kilometres on the tram tracks. The bone setting was done by cutting-edge technology, an Xray movie showing the surgeon where to push the bones. It worked. My little arm does almost everything, and I will remember forever the kindness of the nurses and the way those ambulance drivers stopped Melbourne— just for me.